A Systems Approach to Nutrition

July 16, 2015

For the past few weeks I have attended a joint course by WFP and the NYU Global Institute of Public Health on Nutrition on taking a systems perspective to integrate nutrition, health, food systems, value chains and communities. Here is a summary of the key points of the course.

A Systems Approach to Food Access

- A systems approach – an approach that stresses the interactive nature of the elements, both external and internal – is essential to deal with complexity

- Applied to nutrition, the systems approach means adopting an integrated system linking nutrition (supplementation and fortification), education and health (disease control) systems

- To effectively bring together these systems into a coherent framework, it is essential that each domain understand the meaning of the language used in each domain

Nutrition Fundamentals

- Stunting:

- Shorter height than is expected for age, is the result of chronic undernutrition, can start before birth and is caused by poor maternal nutrition, poor feeding practices, poor food quality as well as frequent infections which can slow down growth. Stunted children are more susceptible to disease, impaired cognitive ability and limits potential

- What to do:

- Prevent at the population level based on risk

- Programming in the first 1,000 days

- Increase the quality of food

- Disease prevention

- In a population with 50% stunting, everyone is below their potential

- To prevent undernutrition, adequate nutrition is a prerequisite, with support depending on the needs (macro- and micro-nutrient deficiency)

- To maximize impact, on nutrition, complement food security interventions with nutritious foods for specific target groups

- Micronutrient deficiency – Iodine, Zinc, Vitamin A and Folic Acid, in particular – is Hidden Hunger

- Nutrition support must be matched with complementary systems:

- Supplementation

- Fortification

- Education

- Disease control

- Key messages:

- 40 nutrients are required in varying amounts

- Dietary diversity is a must to meet nutrient requirements

- Access to a diverse diet is largely determined by purchasing power and availability

- Impact of Special Nutritious Food (SNF) is context-specific and depends on:

- The magnitude of the nutrient gap and the extent to which it is closed

- The impact of disease

- Nutrition during pregnancy and early lactation

Bioethical Issues Around Food Security

- Main principles:

- Autonomy (respect beneficiary wishes)

- Beneficence (promote beneficiary well-being)

- Non-maleficence (Do No Harm)

- Justice (fair allocation of resources)

Systems Thinking for Nutrition

- Key approaches:

- Organizing: Develop participatory, complex, and adaptive collaborative systems

- Dynamics: Understanding dynamic interactions

- Networks: Analyze effective collaborative relationships

- Knowledge: Manage knowledge infrastructure of evidence-based practices

- Systems approaches replaces a Line of Production with a Line of Interaction

- Steps to Systems Mapping:

- Define the problem

- Identify leadership and key actors

- Develop goals and objectives

- Information gathering: available resources, system support, evaluation, knowledge exchange and research

- Advantages of Systems Mapping:

- Organizes diverse perspectives

- Builds consensus among disparate groups

- Conceptualizes an actionable framework

- Prioritizes actions and resources

- Builds partnerships

- Exposes gaps in research and information

Culture

- Different constructs of Community:

- Setting of an intervention

- Target or recipient of an intervention

- Service user

- Service provider

- Resource

- Social Ecological Model (5 levels of interaction):

- Individual

- Interpersonal

- Community

- Organizational

- Policy-enabling Environment

- Food is not just nutrition, but is a social vehicle:

- Social linkages

- Social distinctions

- Symbolic functions and moral significance

- Medium for aesthetic expression

- Classic food ethnographies:

- Single commodities and substances

- Food and social change

- Food insecurity

- Eating and ritual

- Eating and identities

- Instructional materials

- 5 ‘A’s of Utlization:

- Availability: the degree of fit between suitable service and the intervention (right place and time, and meets beneficiary needs)

- Affordability: the degree of fit between the full and the accumulated costs of the intervention and the ability of the targeted individual’s ability to pay

- Approachability: identification and recognition of the services offered by individuals who require them

- Appropriateness: content of the services and interventions v the expectations of those seeking them

- Acceptability: mutual expectations of the service provider and the targeted groups for the services or interventions

Community-based Participatory Research

- Principles:

- Recognize Community as a unit of identity

- Build on strengths and resources within the community

- Facilitate collaborative, equitable involvement of all partners in all phases of partnership and research

- Integrate knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all parties

- Promote a co-learning and empowering process that attends to social inequalities

- Disseminate findings and knowledge to all partners

- Engaging a Community:

- Training: inform about the issues

- Curriculum: focus a dialogue

- Collaborative Leadership Models: share and use many resources

- Practice ethics of hospitality, patience and reconciliation

- Role models: demonstrate how and why an issue is valuable

- CBPR suggestions:

- CBPR training programmes for community members

- Institutional policies that compensate community members for their contributions

- Publicity/publications that highlight organizational involvement

- Institutional support for community service (indirect cost sharing)

- Educational opportunities for members of traditionally marginalized communities

- Recognize CBPR activities in tenure and promotion processes

- Challenges:

- Defining who counts as the ‘community’

- Building trust

- Meeting academic tenure and promotion standards

Nutrition Economics

- Nutrition economics is as much about health outcomes as it is money

- Three point continuum (British Journal of Nutrition (2011), 105, 157–166):

- Efficacy: Does it work?

- Effectiveness: Does it work under real daily life circumstances?

- Efficiency: Is it worth it?

Equity Approach

- Concentration of child deaths in the most deprived communities

- Focusing on the most vulnerable is the most cost-effective approach, addressing both child mortality and stunting, and reducing inequities

- Focus on community empowerment and demand promotion

- Targeted conditional cash transfers

Negotiation

- Trust is best, but not necessary:

- What is needed is commitment

- You need to make commitments the way they make commitments (not the way you do)

- Keys to effective negotiation:

- Goals are paramount

- It’s about them

- Make emotional payments

- Every situation is different

- Incremental is best

- Trade things of unequal value

- Find their standards (people rarely negotiate against their standards)

- Be transparent and constructive

- Always communicate, state the obvious and frame the vision

- Find the real problem and make it an opportunity

- Embrace differences

- Prepare: make a wish list and practice with it

These are my background notes for the presentation I made at the IERP Global Conference in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on 4 June 2014.

I have written elsewhere in this space that emergency managers face four different types of problems:

- Simple

- Complicated

- Complex

- Anarchy

and that, “the solutions to Simple and Complicated problems should be the focus of planning and plans.”

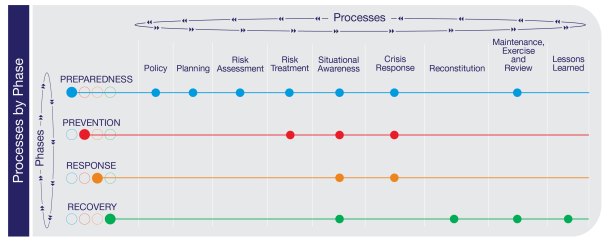

Traditionally approaches to emergency management have been processed-based: a set number of sequential steps that generate the action necessary to prepare for and respond to crisis events, in (hopefully) a virtuous cycle. These approaches are suitable in situations where we have a comprehensive understanding of the factors that underlie the crisis and the way it impacts organizational systems. The question then is what do we do when we do not?

This is a story about complexity and how to deal with it in the context of emergency management.

Complexity

Complexity permeates our lives – like the air around us, we cannot avoid it – and has unique characteristics:

- The output of component systems cannot be anticipated nor controlled

- Component systems interact to produce new equilibria

Under complexity circumstances literally emerge. This means that cause and effect can only be understood retrospectively. Without the ability to expect how systems will interact and how this will impact operations, plans can quickly lose their relevance, like a weather forecast the accuracy of which erodes by the second. We can predict the primary impacts of an event, but doing the same for the secondary and tertiary impacts is difficult. In these circumstances a traditional, process-based approach to emergency management alone is inadequate.

Towards a Network Approach

In a previous post I described and advocated that a dynamic approach to crisis management be adopted, in which constant situational awareness identifies risks and triggers an appropriate organizational response to them. The key crisis leadership tasks the underlie this model are detailed below.

|

Key Crisis Leadership Tasks |

Activity |

| Identify that there is a developing situation that warrants the attention of executive management, and determining how the situation will progress and impact the organization. | |

| Once it has been determined that something is afoot, executive management require support to decide what to do about it. | |

|

Meaning Making |

After deciding the organization’s response, executive management must present a persuasive account of the situation, what will be the organization’s response and gain support for the chosen course. |

|

Terminating |

Transition from an emergency to a normal footing, and providing a retrospective on the situation and gaining consensus around it. |

|

Learning |

Following the termination of a crisis it is imperative that a formal after-action review process be established, and lessons learned identified and integrated into policy, procedure and organizational learning. |

Adapted from Boin, Arjen, et al. (2005). The Politics of Crisis Management [Kindle version] (pp. 217-285). Retrieved from Amazon.com

This dynamic model scaffolds the network approach to emergency management, which recognizes how networks are central to how an organization functions.

Output is produced not just following steps in a business process, but through the interaction and collaboration between networks, formal and informal, within and without the organization. As argued by Dave Gray, a ‘line of interaction’ has supplanted the ‘line of production’ model.

Crises disrupt these networks, or at worst, they collapse, so the aim of the network approach is to develop and nurture them, creating multiple redundancies across organizational and thematic lines.

In practice this means alignment and harmonization in four areas:

- Common understanding of risks that can lead to crises

- Plans and planning processes

- Governance and implementation structures

- Behavioural change.

Under this approach:

- Decentralize risk management, but govern it centrally

- Risk management dynamic, focused on identifying vulnerability in operational risk areas (people, processes and systems)

- Integration, integration, integration

A network approach to emergency management is not only effective in circumstances of complexity, but it generates value for an organization by:

- Creating serendipitous effects

- Improved risk management

- Increased efficiency from process re-engineering

Conclusion

A process-based approach to emergency management has intuitive appeal because it has a defined, limited scope with discrete, measurable deliverables. Conversely, a network approach is messy and its components, especially the informal collaboration networks, are unknowable, meaning that measurement is almost impossible (I qualify ‘impossible’ because you can hold out examples of serendipitous effects as evidence of value). And yet it is clear that an emergency management programme is vulnerable it does not include an emergent strategy to nurture and strengthen collaboration networks.

Related stuff that I am working on

- How do you govern a network?

- How do you value the output of a network?

- How do you cost a network?

BCM World Conference 2013: Risk Management and Business Continuity

November 18, 2013

Again this year, I made the pilgrimage to London to attend the BCM World Conference and Exhibition; a link to the background paper for my presentation is here.

As always, there were some nuggets. Here is one:

Risk and Business Continuity (Mike Power – LSE)

Professor Power cogently described how Business Continuity Management can contribute to effective enterprise risk management. He began by detailing the challenges to manage enterprise risks:

- The Illusion of Control, characterized by the assumption that we have more of an understanding of cause and effect than we really do. As I have written elsewhere, in complex and anarchic events, cause and effect can only be understood after the fact

- Fragmentation of capability to manage specific risks

- Entity v System Focus, resulting in organizational stove pipes

- (Unrecognized) Interconnectedness, concomitant with today’s complex systems

Power then turned to the challenges for Business Continuity Management in the enterprise:

- BCM has historically been disempowered, considered overhead and not a value-generating part of the business

- The slow emergence of operational risk

- Weak institutionalization, stemming from the perception that BCM has only an operational or technology focus

- Weak accountability within the enterprise for low probability-high impact events, which are the bread and butter for BCM

To respond to these challenges, Professor Power proposed a number of solutions:

- Establish and formalize the Three Lines of Defence: Business, Corporate Risk Management, and Internal and External Audit. These lines are graphically depicted at Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Three Lines of Defence

- Identify the scenarios under which your organization will fail . . . completely, and then decide what will be your strategies to recover from catastrophic loss

- Establish a risk culture – the ability to think of alternate futures and build action plans around them – where:

- The authority for risk and control functions are clear

- There is a respect for controls

- There is close attention to incentives risk

- Accept that you can do your best, but there is still a chance for failure

- Recruit charismatic BCM leaders

- Build the narrative of BCM’s value generating capacity:

- Embed resilience as a core organizational value and ‘BAU’

- Circulate stories of success

- Create the discourse, incorporating the performance nature of language: if you talk in a certain way, it will happen

- Incentivize collaboration: when the world is moving against you, to succeed, collaboration must increase.

My Take

Professor Power’s presentation resonated with me because the content was consistent with my experience. First, there is a common bias toward a programme, or entity, approach over a system approach. This in turn complicates the management of operational risk, which can only be done effectively by an enterprise approach. Second, it is ironic that fragmentation features in a field – emergency management – in which consolidation is almost always a good idea.

Third, there is a critical message implicit in the Three Lines of Defence: corporate BCM can support businesses prevent, prepare, respond and recover, but each business is responsible for their continuity and resilience.

Finally, BCM is a value generator. The focus of BCM is to find and preserve value within the organization. Executing this responsibility, connects BCM with all parts of the enterprise, inevitably generating serendipitous effects that are typically of significant value. Any time you have a conversation around risk, good things happen.

Related articles

- Organizational resilience at the United Nations Secretariat (buridansblog.com)

- Reflections on BCM World 2013 (crisisthinking.co.uk)